Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Despite being named the Hope Conference, many attendees have a complicated relationship with the word hope.

Those who gathered at the Salt Lake County Government Center on Saturday, about 50 in total, are the loved ones of the missing or murdered, an extensive network of victims of violent unsolved crimes.

"Never give up hope," said Salt Lake County Sheriff Rosie Rivera. "Times change, technology changes, people come forward." But some families who have waited a decade or more with no justice in sight struggle to stay positive.

"I don't like to get my hopes up," said Jenna Griego. Her mother, Alice Griego, 55, and her mother's boyfriend, Ralph Salazar, 59, were shot and their bodies set on fire in December 2012. "You get your hopes up and you still have to continue to get hurt, and I hurt every day on this," she said.

"It doesn't seem like 12 years. It actually seems like it just happened yesterday," Griego said. "I relive the day, every day in my head."

There are 440 cold cases in the state's database, according to Kathy Mackay, an analyst for the Statewide Information and Analysis Center. On Saturday, she and other officials presented a number of reasons why families should remain hopeful.

Between 2018 and 2023, 28 cold cases have been solved, Mackay said. But in 2024, there have been 15 cases solved, with more coming. "This should give you hope," she said.

Part of this uptick in solved cases can be attributed to the hard work and resources coming from the Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office. Detective Ben Pender, who's entire job is working cold cases, says, "It's really the support that I have from the County Council, the sheriff, the administration, that allows me to be able to work these cases and do what I need to do."

"I can honestly tell you that I have never been told no when it comes to any testing. I have never been told, 'No, you can't go out of state to conduct an interview,'" he said.

Pender worked with the Department of Corrections to distribute thousands of decks of playing cards to inmates around the state, with information on unsolved cases on each card, hoping that information would surface.

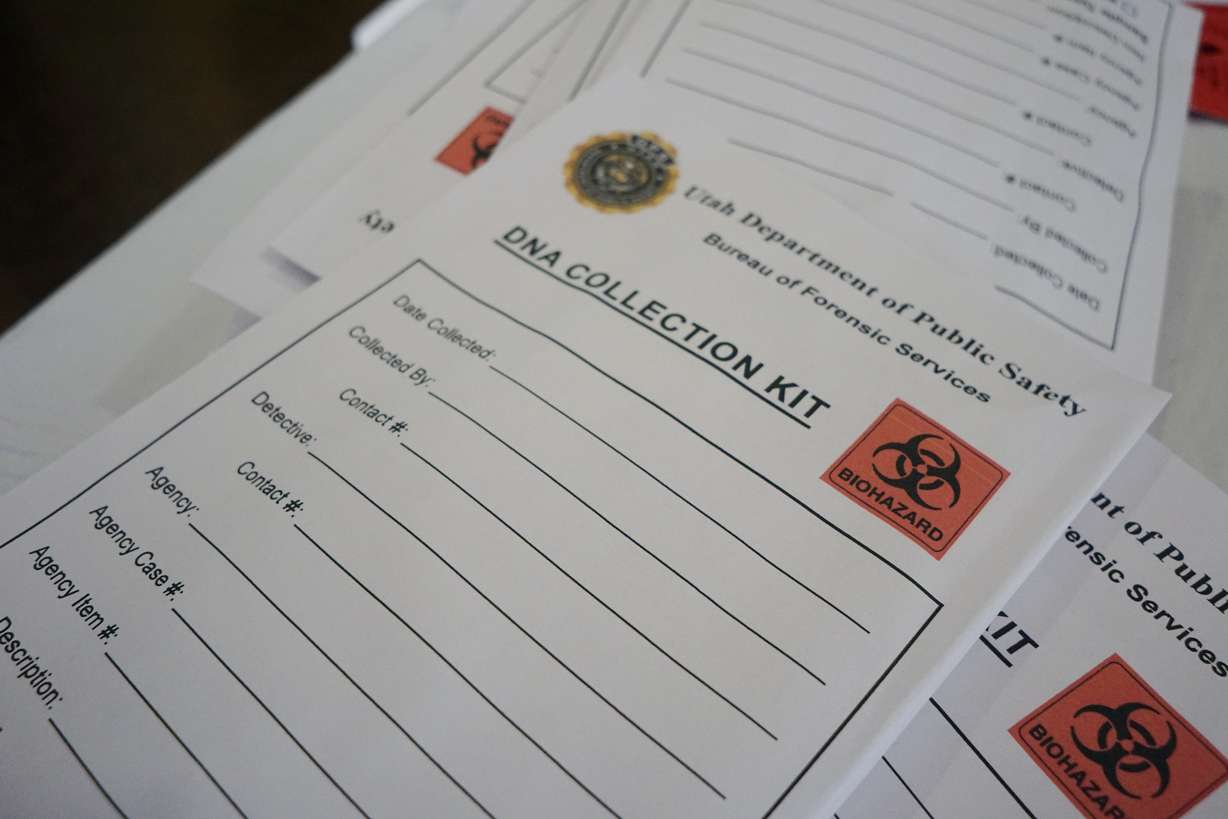

Another reason these families should have hope is the constantly evolving forensic technology at play. In 1992, the state crime lab began DNA tests, which required 250 nanogram samples, according to Rebekah Kay, a senior biology manager at the Utah Bureau of Forensic Services; 250 nanograms is a quarter-size stain of blood that has to be from a single individual.

Fast forward to the present, and a sample requires just 0.5 nanograms of genetic material. Investigators can pull trace amounts of DNA off the sweat stains of an old shirt, or a briefly held bottle of water. Software can tease out up to four different individuals' genetic profiles and identify family members to the 5th cousin.

Technology can look at the part of ethnicity that is biologically determined to find race. Phenotyping can identify several externally visible characteristics like eye color.

"It's just changing at a rapid pace. It's something that we have to work at the crime lab to keep up with because as soon as we get one technology online, they're already looking to advance the technology, which we then have to bring online to use in cases," Kay said. "So, it's an ever-changing field at this point in time, which should also bring a lot of hope with it because there are more advancements coming. This is not a stagnant science."

Private labs are currently developing enhanced DNA recovery and sequencing methods, some of which may require just a single cell in the future.

But many of these crimes happened at a time when investigators had no knowledge of DNA testing. Samples may never have been collected, may have been stored improperly or contaminated.

A large challenge, explained by both Pender and Kay, is the decision to test the small bits of evidence in each case. They might only have the ability to test the evidence once or twice and must decide whether to use current technology or wait for better methods to develop.

"We just have to try to weigh what's best for the evidence in order to answer the questions of the case," Kay said.

Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill also spoke at the conference. He said that in the last five years, "our offices filed on six cold cases, going from five years to 28 years ago, and we resolved two of those." Gill said that the result of one case was life without parole, but it took almost 10 years to solve. Four other cases are currently pending.

The waiting, however, takes a significant toll on the family of victims.

"There was a time in my life where I never stopped fighting for my mom," Griego said. "It was like every year I would reach out to the news. We did press conferences and I was always advocating for her, always wanting to get justice. And when it hit the 6 or 7 year mark, I felt powerless because I didn't feel like anything was coming out of it."

"You get tired emotionally, physically," she said, but "felt like my mom was telling me, don't give up, you know. So I'm going to continue to advocate for her and continue to be her voice — continue to fight for justice for me and my family."