Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

WEST VALLEY CITY – When Barbara Boynton started feeling tired and weak in 2015, her wisteria was blooming by the front porch where she spent summer evenings with her grandchildren.

By the time doctors found out what was wrong with her lungs, her yard was covered in frost.

Boynton was diagnosed that winter with mesothelioma, a rare cancer with only one known cause: asbestos. She died less than a month later.

Boynton never worked around asbestos, the mineral used in chalky insulation decades ago at construction sites or industrial plants. But her husband worked in those settings early in their 54-year marriage.

"Now that it's done and over with, it's very understandable to me that you're going to work and you're hauling that stuff home," Larry Boynton said. "You didn't think you was hauling anything home that was going to do what it done, caused the grief it caused."

He tracked the asbestos back home to West Valley City on his work clothes, and Barbara Boynton shook them out before she washed them. Now he says that dust robbed him of his life partner.

A long legal fight

Barbara Boynton's death is now at the center of a lawsuit her husband hopes will change how companies operate. An early decision in the case has already had far-reaching impact, allowing others like him to move toward a trial.

That development sends a strong message to employers, and not just where asbestos is concerned, said Larry Boynton's lawyer, Rick Nemeroff.

"This tells a company, your problem doesn't just end at the company gates. If it leaves the gate and goes home in the car to the family home, your responsibility didn't end. You've got to look further than that," Nemeroff said.

The KSL Investigators found the question who's responsible for second-hand exposures is at the heart of other cases across the country.

Families like Larry Boynton's have won recent cases in Louisiana and Alabama. But courts in Georgia and Arizona have ruled that if you're not the company's employee, you're not the company's liability.

When Larry Boynton first sued in 2016, Utah hadn't yet settled that question.

Ruling in his case in 2021, the Utah Supreme Court provided an answer. The court found by the early 1960s "there was substantial scientific evidence" suggesting take-home exposure was "sufficiently foreseeable."

The companies where Larry Boynton worked had a duty to "exercise reasonable care to prevent take-home exposure to asbestos," so they can potentially be held liable for such exposures, the court's opinion states.

The case instructs courts in Utah, but it also helps give direction to other states grappling with the same questions, Nemeroff said.

A verdict and push for a new trial

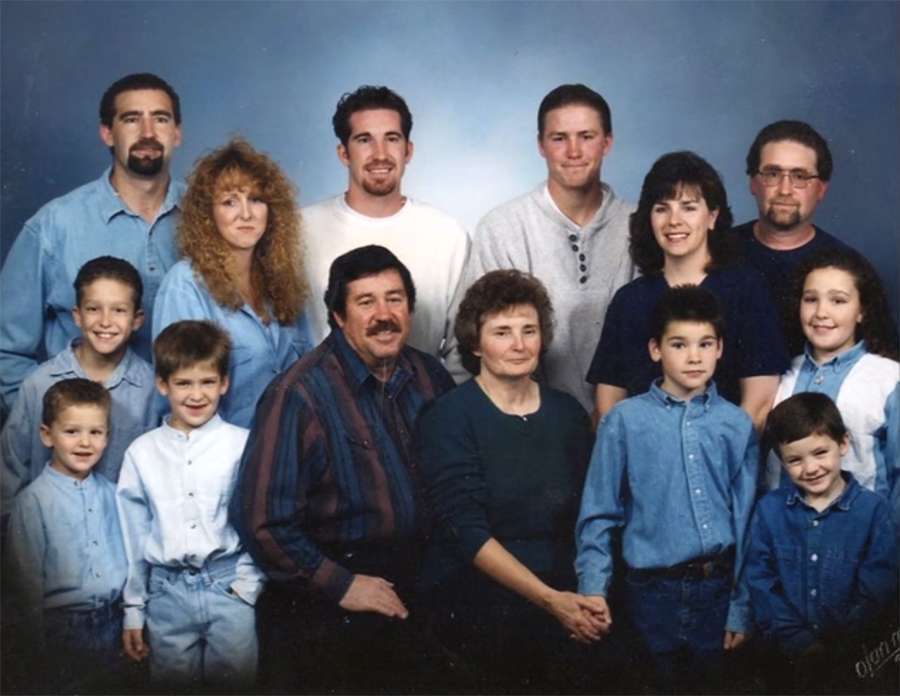

Larry and Barbara Boynton raised four children together and spent weekends going to estate sales, bringing home antique clocks, and taking long drives. Outgoing and warm, she especially loved dressing up with her grandchildren as witches at Halloween, her husband recalled.

When it came to him, she displayed her affection in small ways.

"Every morning I went out the door to work, she'd give me kiss and send me out the door," Larry Boynton recalled. "And she didn't miss any days."

He worked various construction jobs in the 1960s and part of the work included raking up chunks of old insulation made of asbestos. Later he became an electrician.

Larry Boynton said the asbestos dust was constant, but the companies didn't require respirators or on-site laundry to keep the dust from going home to their families.

"We had no idea anything was bad," he said. "Far as we went, she was just laundering my dirty clothes."

He originally sued roughly two dozen companies that sold, used or made products of asbestos he worked around. Some paid to settle the cases, while others were dismissed. He's still fighting his case against one: Kennecott Utah Copper.

This year a jury found Barbara Boynton breathed in asbestos that came from Kennecott but found the company wasn't negligent. But Larry Boynton is still fighting and asking for a new trial.

"They should be held responsible," Larry Boynton said.

Kennecott's owner Rio Tinto declined to talk about the case while it's pending. However, in an email to KSL, it said the company prioritizes safety, provides protective gear, and trains employees in detail on workplace risks.

"Nothing is more important than the safety and well-being of our employees, contractors and communities," the statement reads. "We adhere to all regulatory standards and implement stricter company standards to ensure the highest level of health and safety."

In court for the Boyntons' case, attorneys for Kennecott argued it's not responsible. Lawyers for the company said that when Larry Boynton worked there as a contractor, the dangers of products made from asbestos – and the hazards they can pose to family members and the public – weren't clear.

Larry Boynton's lawyers contend the company's own reports and other documents from 60 years ago dispute that.

For example, the records indicate Kennecott sent a safety officer to Pennsylvania in 1961 for training on job site hazards, including asbestos and its ability to infiltrate the lungs. But Larry Boynton's lawyers say the knowledge from that training didn't translate to protections for him.

Kennecott argues even if he does get another trial, it wouldn't change the outcome. A judge hasn't ruled either way yet.

Looking beyond asbestos

Tom Burke, a past science adviser for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and an expert at Johns Hopkins University, said he sees parallels between asbestos and toxins of today.

"We know that not just asbestos, but other toxic substances can be brought home," Burke told KSL.

For example, farm workers who spray pesticides may wear a respirator to protect their lungs on the job, Burke said, but they may very well wear the substance home on their clothes and then hug their kids, exposing children to those chemicals.

The EPA banned asbestos in the U.S. and the Utah Supreme Court provided an answer after several stages of partial bans.

But Burke said there are smaller steps that can go a long way in reducing health risks of other toxic materials.

"Asbestos is a great historical lesson," Burke said, in illustrating the importance of protecting not just workers but their family members and the public.

"Unfortunately, they were lessons learned the hard way," Burke said, "but lessons we can't forget that affected workers and families very dramatically."