Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

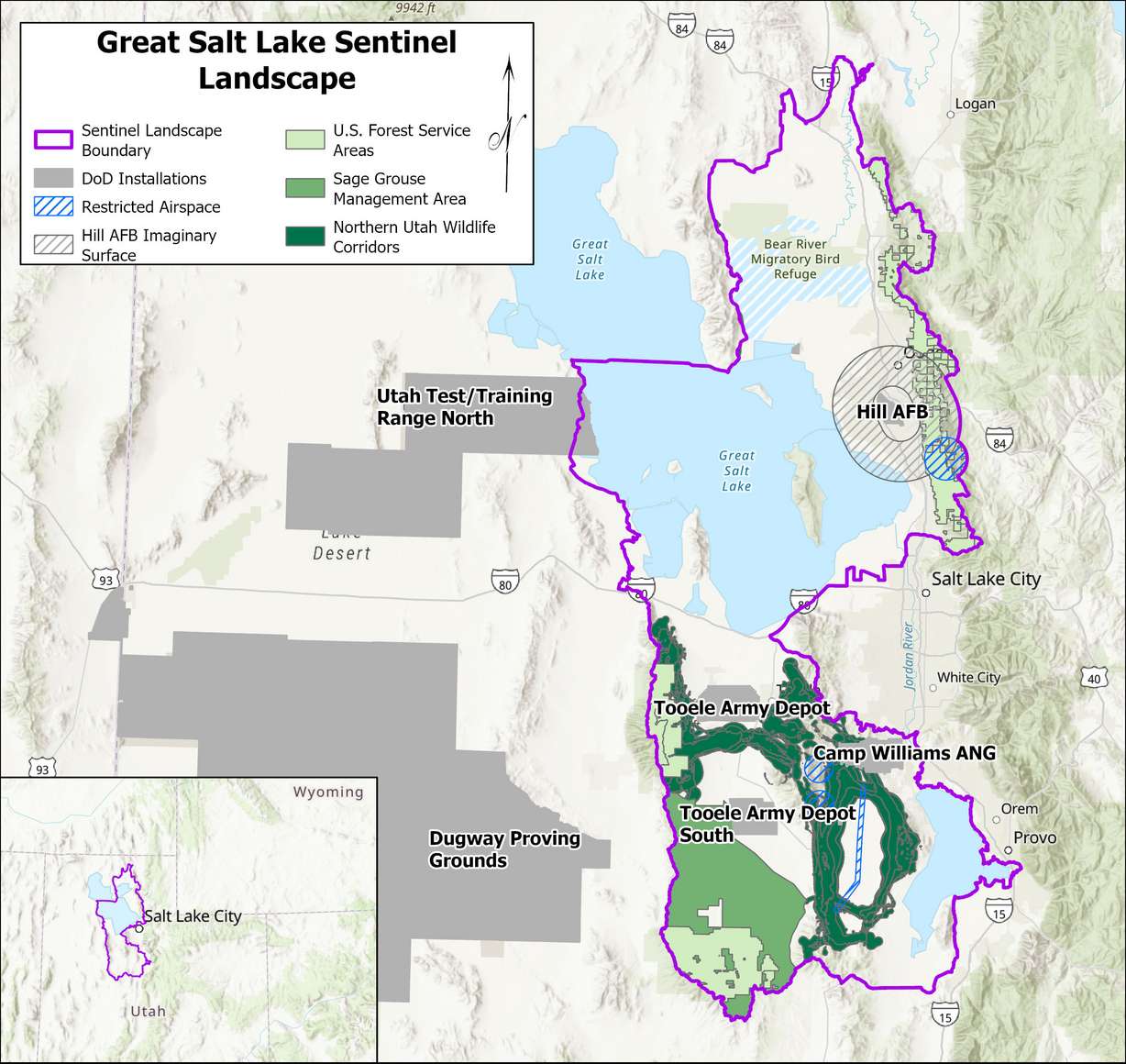

SALT LAKE CITY — A 2.7-million acre swath of northern Utah has been designated a "Sentinel Landscape" by a trio of federal agencies hoping to leverage a kind of cooperative land management policy to combat the encroachment of development around military installations.

Utah's new "Great Salt Lake Sentinel Landscape" is one of five state area applications accepted this year, along with New Mexico, California, Hawaii and Pennsylvania, for a total of almost 10 million acres.

It encompasses military sites along the Wasatch Front, including Hill Air Force Base, Tooele Army Depot and Camp Williams, but also important natural areas. The Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, the southern half of the Great Salt Lake and all the way down to Utah Lake are marked out.

The designation is part of a partnership that has grown in influence and participation in the last decade, bringing a large group of organizations together to connect the funding and goals of military installations with conservation projects in its boundaries.

Military installations have historically been placed far from population centers, according to Tyler Smith, former commander of Utah's Camp Williams and coordinator of Utah's new sentinel landscape.

"As population density started to move out into the rural areas, all of a sudden, military installations started to have what's referred to as urban encroachment of incompatible development," he said.

The "booms and bullets" and other hazards of training began creating problems for the new family subdivisions, apartments and schools. "As the military prepares to deploy and fight our nation's wars, it really inhibits military readiness when there's this kind of incompatibility that occurs around military bases," Smith said.

In 2002, Congress began appropriating funds for the Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration Program, which aimed to secure buffer zones around installations, so realistic trainings and weapon systems testing could happen without having to travel. According to Smith, the program had success, but "it just simply was not enough to keep pace with the development."

The Sentinel Landscape Partnership, beginning in July 2013, took a similar approach to its predecessor with the U.S. Department of Defense, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Interior working together to prevent "incompatible development" from occurring near bases and testing sites. Most of this happens in the form of land conservation projects, securing easements and open spaces that prevent building.

The goals of the Salt Lake sentinel landscape include preserving the migration corridors of birds and deer, protecting water sources, and mitigating the risks of wildfire. Numerous private, local and state organizations are already agreeing to participate as a way to connect funding sources and expertise. It's like a giant trade organization that allows these groups to connect resources and talent.

The designation will also open up more avenues for funding, as there is explicit language in the National Defense Authorization Act prioritizing funding for sentinel landscapes.

"It's not just about military readiness," Smith said, "it's about creating a landscape that's resilient for all that exist within that boundary."