Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

EDEN, Weber County — As snow fell hard and heavy on the Wasatch Mountains, six wildlife scientists from the Department of Wildlife Resources crouched in the vestibule of a Powder Mountain condo Thursday, watching and waiting for an elusive species of alpine finch to wander into their trap.

Clark's nutcrackers called from the aspen grove across the street, while chickadees darted in and out of the opening to the cages, grabbing the seeds scattered as bait. A string tied to a stick propped open the door to a green mesh trap ran about 20 feet, to where Kristin Purdy, a self-described "bird nerd," waited inside the door, ready to yank the trap closed when the time was right.

Purdy, a volunteer who oversees logistics at the Powder Ridge Condominium site, says she puts out about 600 pounds of bird food in nearby feeders every year, a quantity hard to believe, judging by the 30-gram animals hopping around.

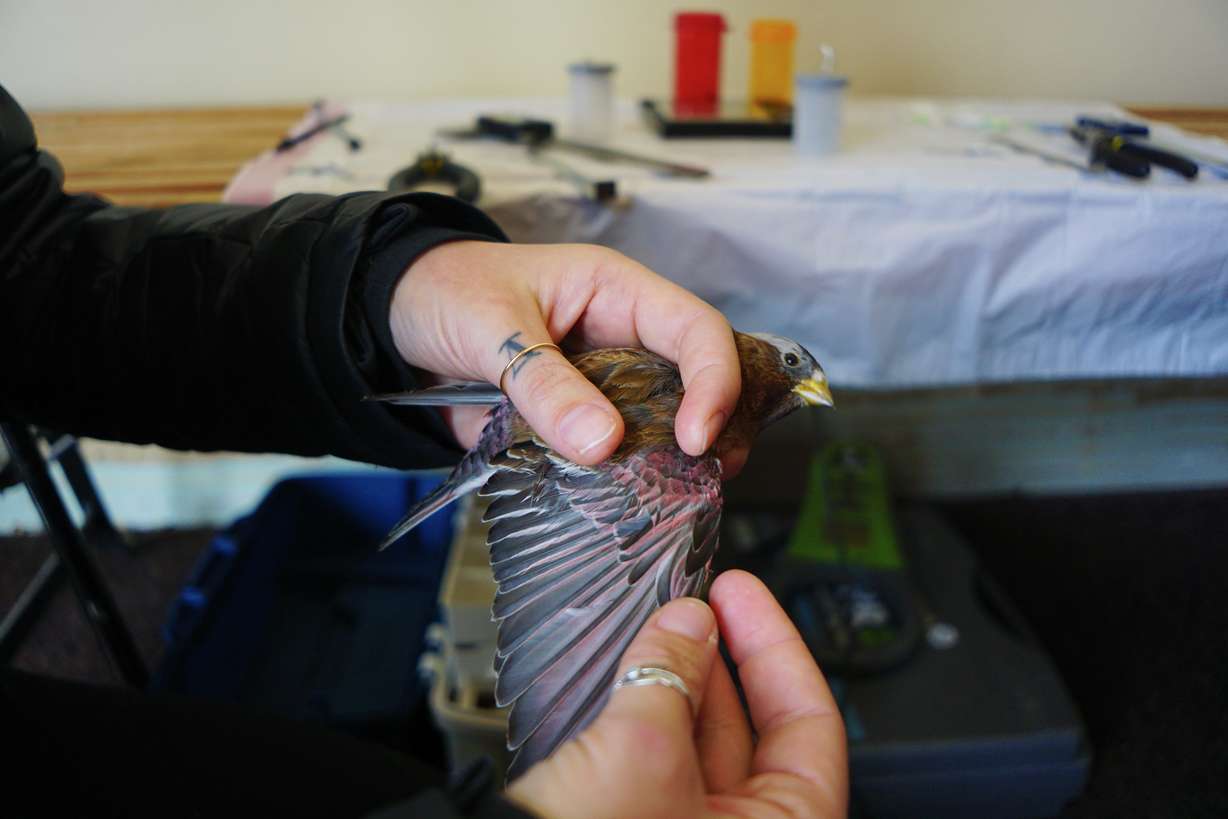

The team was hoping to capture and tag as many rosy finches as they could, one of the least studied species in North America. Inside the small entryway to the ski lodge, they set up stations to place metal tracking ankle bands and radio-frequency identification tags on the captured birds, as well as scales and calipers to measure demographic features.

Estimated age, weight, gender, feature sizes and more are recorded in a federal database, so if they're caught again in Alaska or Montana, scientists can access that data.

Birds cheerfully flew into the traps to supplement their winter diets, while the crowd of onlookers hoped winged predators, like the falcons seen recently, stayed away. If they show up, the birds on the ground become scarce and stay that way for hours. A pair of chickadees got too rowdy, springing the trap on themselves, and were brought inside for banding.

"When we're talking about rosy finches, we're talking about a group of species, what are called a super species," biologist Adam Brewerton says. The team is on the lookout for two of the species, the gray-crowned variety and the rare black rosy finch.

According to Brewerton, these "living dinosaurs" are very understudied for practical reasons. They're highly nomadic, which makes data collection and comparison difficult, and many of these little birds that appear so carefree live in some of the most extreme environments on the continent. The gray-crowned species are known to nest high above the tree line, in crevices and cliff faces on the slopes of Denali, and in alpine environments even farther north.

Just weeks after the birds hatch, usually in early summer, their flight feathers are all grown in, and the adolescents are learning to catch bugs and dig for seeds. By fall, when it is time to migrate toward their wintering habitats in the western United States, they are fully independent. As they eat insects with keratin in their exoskeletons, the coloration in the bird's wings and breast grows more red, the same way flamingos turn pink by eating brine shrimp and algae.

The biologists only spotted one black rosy finch in the dozens of gray-crowned birds caught in the traps. It never entered the cage but had been tagged earlier this season. The black mountain finches breed in the high-altitude environments of Utah, and a handful of other western states, making ski resorts an ideal location for bird observation and tracking. Another location at Alta does the same work, capturing and banding birds from January to the end of March.

The Powder Ridge Village Condominium began hosting bird feeders for the Department of Wildlife Resources scientists starting in 2009. The rosy finch project has grown since then. It has become a public-private collaboration, with partners at the Tracy Aviary in Salt Lake City, the Sageland Collaborative and the U.S. Forest Service.

Under the North American model of wildlife management, Brewerton says, "A lot of wildlife conservation has really been championed and pioneered by hunting and fishing."

Hunters and anglers have a long-standing tradition as conservationists, but it has naturally been geared toward populations that can be harvested, like waterfowl hunting in wetland areas. Non-game conservation projects have to take a different approach to find resources for study and observation.

"If we can answer questions about survivorship, longevity, demographics, find out where they go, where they come from, those are all little pieces of a puzzle that can tell us why the populations are declining," Brewerton said.

Ornithologists, or scientists who study birds, are still learning a great deal about migration patterns, lifespan and population sizes.

The super species' habitats are in some of the areas hypothesized to be most affected by changes in climate, and research can provide early indicators of significant shifts in the environment.

"One of the things that make birds so cool is that they're a truly global species," Brewerton said. "And if we can identify that their survival rates are affected by one part of their life cycle versus another, we can focus our conservation efforts."