Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY — Underground water is vital to Utah's water cycle and supply.

It accounts for up to a quarter or more of the water in some communities in Utah, which is significant, says Hugh Hurlow, manager of the Utah Geological Survey's Groundwater and Wetlands Program.

However, as important as it is, how it functions isn't as well known as lakes, rivers, streams and any other above-ground bodies of water. While explorers first began mapping the state's above-ground water features as early as the 1840s, Hurlow points out that many of the first state papers on underground water only date back to the 1960s.

Work has been done since then to chip away at the mystery, and a comprehensive new website collecting all of that may help policymakers make future decisions tied to underground use.

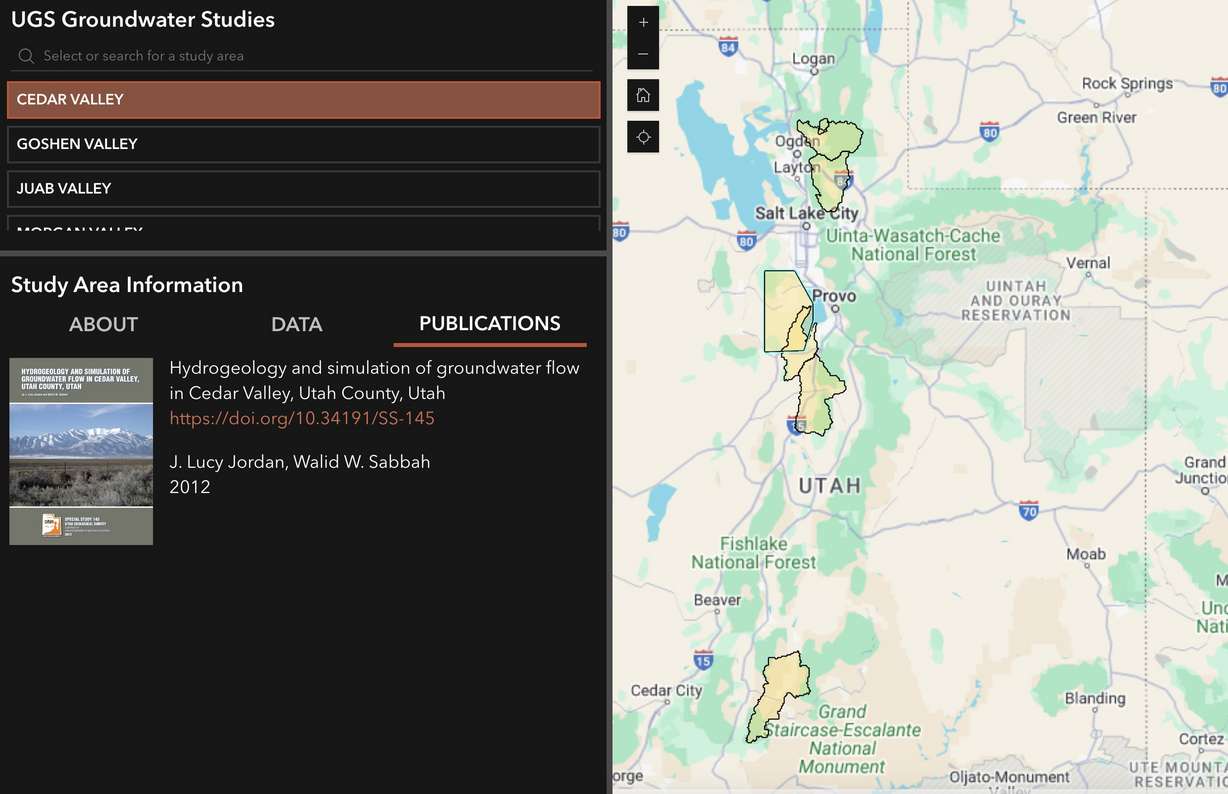

The Utah Geological Survey launched the Utah Groundwater Data Hub on Tuesday, which compiles existing state and federal groundwater data, maps and studies into one website. That includes some information that was previously unreleased or unpublished online. Hurlow said a small team of employees spent "hundreds of hundreds of hours" to digitize records and build out the site.

It sheds light on how underground water has changed within a section of western Utah. There are also a handful of studies on groundwater in areas like Powder Mountain in the Ogden Valley and Bryce Canyon in southern Utah, as well as a full section on the Great Salt Lake. More areas are expected to be added in the coming months.

"This is the first step in moving our data to a more accessible format," Hurlow said.

The mystery of groundwater

Groundwater isn't a complete mystery, but researchers are still making discoveries. Hurlow explained that many modern wells date back to the 1930s, which seems to suggest people were aware of Utah's underground water potential back then.

Records — many of which are now being digitized for the first time — show that state agencies began to truly study groundwater in the 1960s. This continued up until the Groundwater and Wetlands Program was created in the 1990s, becoming a Utah Geological Survey focus.

Studies helped fill in many knowledge gaps, but Hurlow says groundwater isn't as "directly measurable" as above-ground water, so it's harder to know some answers with certainty.

Experts know that long-term groundwater yield is dependent on recharged aquifers. There's also some sort of relationship between soil moisture and groundwater. When soil is dry from a lack of precipitation, water from the state's snowpack goes toward recharging groundwater before melting into the waterways that flow into the state's reservoirs.

The depth of this relationship and underground capacity are still being explored, though. Members of the Great Salt Lake Strike Team, a group of state and higher education researchers, said in January they were surprised to find that a good percentage of last year's record snowpack in the Great Salt Lake Basin went toward groundwater reservoirs even when soil moisture levels reached record highs.

It seemed to indicate that the underground reservoirs within the basin weren't fully recharged despite much better conditions.

"This is a key piece of the hydrology that tells us how much water ends up in the streams, ends up available to society and ultimately ends up going into the lake," said Bill Anderegg, director of the Wilkes Center for Climate Science and Policy at the University of Utah, at the time.

The team is now tracking the basin's underground water. The Utah Geological Survey also began work earlier this year to establish a groundwater measurement network in and around the lake that had never been consistently studied before.

It's a fraction of the ongoing work happening across the state.

Collecting this type of data and analyzing trends may help researchers better predict snowmelt runoff efficiency in the future, which matters because 95% of the state's water supply comes from the snowpack collection and spring snowmelt process. It can also better predict how much water ends up in places like the Great Salt Lake.

Compiling data into one source

But it wasn't until last year that a large-scale effort was made to compile all of this information into one online source. The Utah Legislature directed $320,800 to create the website during the 2023 legislative session, noting that it would be used to help the Utah Division of Water Rights make water decisions.

At least three more survey study areas will be added this year as the team continues to build the site, Hurlow said.

He believes it could become a valuable resource for others beyond state agencies, as it offers a better picture of Utah's full water supply. It may also help communities make decisions themselves.

Available trends show a decline in groundwater over the years. It may force communities to dig wells deeper into the ground, find new sources of water, or prepare for other types of impacts. Parowan Valley is one example that comes to mind.

"They're getting to levels where they're really going to have to adjust in some way," Hurlow said, explaining that agriculture water use is a big contributor to the depleted water there.

Some communities, he adds, have already implemented programs to purposely get water back into underground storage. South Jordan Water District does this for wells, while the Weber Basin Water Conservancy District has a small program that sends water to aquifers by Weber Canyon.

It's a trend that may also grow as groundwater slowly becomes less mysterious.

Contributing: Lindsay Aerts