Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Great Salt Lake Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative that partners news, education and media organizations to help inform people about the plight of the Great Salt Lake — and what can be done to make a difference before it is too late.

SALT LAKE CITY — A team of Utah agencies and research institutions outlined six "major" recommendations for the state to consider when it comes to handling the drying Great Salt Lake, and offered insight into the impact and feasibility of solutions already suggested — or in motion.

But failing to address the lake's decline poses threats to public health and economic activity in Utah in addition to the ecosystem that relies heavily on it, members of the Great Salt Lake Strike Team wrote in their first policy report issued Wednesday. The report also urges the state to act quickly because the lake has already fallen to levels that could come with "serious adverse effects."

Brian Steed, director of the Janet Quinney Lawson Institute for Land, Water, and Air at Utah State University, and a member of the strike team, calls the report both "stark and hopeful," in that it highlights the concerns of the lake now but offers steps on how those impacts can be reversed.

"We are indeed in a very troubling situation ... and we have choices to make," he said. "What the hopeful portion is ... realizing that we're dire times on the lake but it has to be a motivator for us to actually then take action."

How the lake fell

The main purpose of the study was to showcase how the lake fell and what can be done to reverse its downward trajectory, said Bill Anderegg, director of the Wilkes Center for Climate Science and Policy at the University of Utah. It's meant to guide Utah policymakers in their decision process instead of telling them what to do because there isn't a single solution that will help reverse the Great Salt Lake, Steed adds.

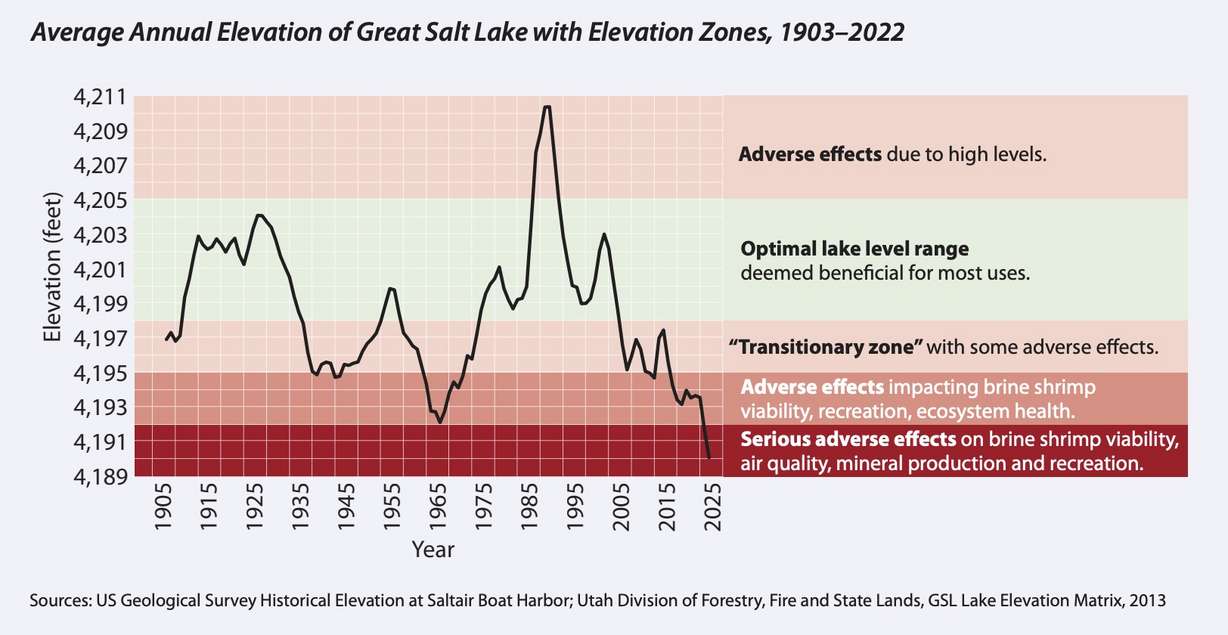

The Great Salt Lake has experienced ups and downs ever since levels were first tracked in 1847. But the report lists 4,192 feet elevation as the point where "serious adverse effects on brine shrimp viability, air quality, mineral production and recreation" are possible. The lake crossed that line in 2021, continuing to fall to a record low of 4,188.6 feet on Oct. 27, 2022. It has risen some since but remains well below this target.

The biggest reason for this drop isn't much of a surprise. The report finds consumptive use is by far the leading factor, accounting for anywhere from 67% to 73% of the lake's decline. It towers over other detractors like natural variability, or the uncertainty of snowpack collection and snowmelt runoff, which accounts for anywhere from 15% to 23% of the decline, or direct evaporation, which accounts for 8% to 11% of the lake's water loss, according to the report.

Projects that divert water from the lake's tributaries are a major reason why water isn't going to the Great Salt Lake, the report adds. The Bear, Jordan and Weber rivers account for nearly 95% of the lake's water; however, not as much of the water of those tributaries is ending up in the lake.

It's going to be hard and it's going to take resolve, urgency and commitment over a long period of time but it's doable.

–Bill Anderegg, on if the Great Salt Lake can be saved

Anderegg notes that continued warming temperatures may cause evaporation to rise in the future, and the findings offer insight on how much that can change in the future. Yet working on the study changed his perspective on the future of the lake, leaving him more "optimistic" about the situation because the situation can be addressed through tools available now.

"It's going to be hard and it's going to take resolve, urgency and commitment over a long period of time but it's doable," he said. "I think this is our window of opportunity. This year, next year and the year after matter enormously."

6 steps to consider now

So can Utah save the Great Salt Lake?

Members of the team — leaders and researchers from the Utah departments of agriculture, environmental quality and natural resources, as well as researchers at USU and the University of Utah — said the state can start by taking advantage of this winter's above-normal snowpack. This year's snowpack is still forecast to end up between 110% and 130% of normal, according to the Utah Division of Water Resources.

"The current wet year offers a significant opportunity to make progress on the lake elevation. Do not miss this opportunity," the team wrote in the report.

But given the massive deficit the lake faces, Candice Hasenyager, the division's director, warns this year's snowpack alone won't fix the issue. This step is more along the lines of maximizing good water years because, as she put it, "we have a lot of deficit to make up from this long-term drought we've been in."

The five other recommendations in the report are:

- Set a lake elevation range goal between 4,198 feet and 4,205 feet elevation

- Invest in water conservation to increase inflows or decrease withdrawals from the lake.

- Invest in water intelligence monitoring and modeling, so the state can be "more responsive and effective to challenges." The team recommends that the state double its current investment in "accurate and timely measurements and forecasts."

- Develop a long-term water resource plan for the Great Salt Lake watershed basin to "ensure a resilient water supply for all water users in the basin, including Great Salt Lake." The Utah Department of Natural Resources is currently developing this.

- Request in-depth analyses on policy options, so that the Utah governor and Legislature can direct the Great Salt Lake Strike Team to study the most water-efficient, cost-effective and high-return options.

What are long-term solutions that work?

The team also analyzed some of the solutions that have already been proposed to fix the lake's issues, offering a look into benefits, costs and challenges, and feasibility.

For example, importing water to the Great Salt Lake through a pipeline could bring 500,000 acre-feet of water every year, making it the best option in terms of lake-level benefits. However, the team also notes that such a project would be "expensive, slow and controversial," likely costing more than $100 billion and taking decades to complete.

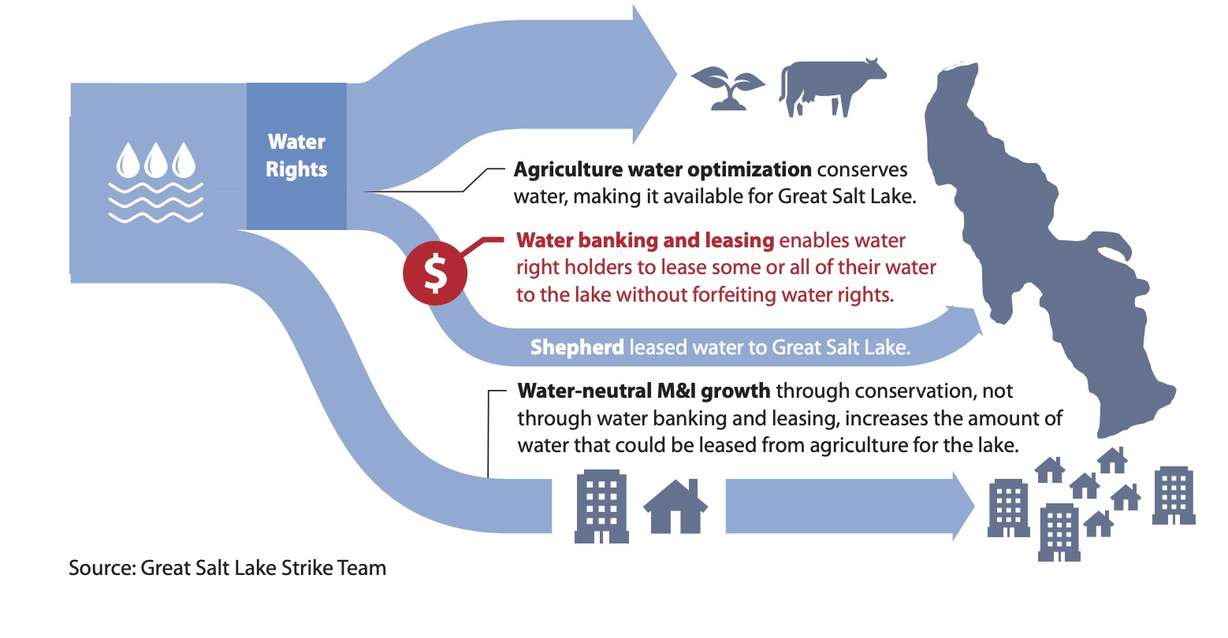

They contend the Great Salt Lake Trust and optimizing agriculture water use are more feasible options — on top of general conservation across the board. Neither project would bring in as much water as a pipeline but both rank much higher in feasibility, and would still bring in more water than ideas like optimizing mineral extraction water use, cloud seeding or thinning the forest trees in the Great Salt Lake watershed.

The other benefit is that both are already in motion. The Utah Legislature allocated a record $70 million to the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food's Water Optimization Program in the 2022 legislative session, and $40 million to the trust.

It's why members of the strike team said Wednesday they'd explore expanding these options first if they were given the funds right now.

The Utah Department of Natural Resources is seeking another $200 million in state funds to boost the statewide program, which would benefit water conservation across the state, said Joel Ferry, director of the Utah Department of Natural Resources and a strike team member.

Wednesday's report finds that agriculture optimization can reduce water use by 10% to 15%. About 180,000 acre-feet of water would be saved every year if all agricultural use was cut by 15%. One acre-foot of water equates to about 325,851 gallons of water.

This strategy ultimately makes sense for farmers, too, Ferry says. As a farmer himself, he began looking at optimization technologies in an effort to have more efficient yields as water uncertainty began messing with business.

"I wanted to make sure I had stability with my business," he said, adding that these tools allow farmers to be as productive with less water.

"When we talk about overall conservation being 15%, that's not cutting back production necessarily," he said. "That's making (an) investment."

Meanwhile, they find there is a potential to lease 200,000 to 300,000 acre-feet of water through the Great Salt Lake Trust. The program allows for water rights owners to lease their rights so the water flows into the Great Salt Lake without the owner losing their rights permanently. It simply requires anyone with water rights to agree to lease their rights.

The Utah Legislature's $40 million trust is expected to begin seeking inflow additions this year.

What happens next?

State leaders will ultimately have to pick the solutions they want to implement in the end, though. Steed said the strike team plans to continue studying the lake and options to preserve it, so lawmakers have the best available data to pull from as they mull every option.

Members of the team say they are hopeful that state leaders will consider all of the options and act quickly as they seek to refill the lake, given what's at stake if they don't act on it all or if they act too late.

"We have control of a lot of our future here," Anderegg says. "The decisions that we make as a state really have a huge impact on what the future of the Great Salt Lake will be."