Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Federal officials are calling on states along the Colorado River Basin to continue to conserve as much water as possible while unveiling a plan to keep the two largest reservoirs in the country functional in 2023, as both struggle to retain water amid a changing climate.

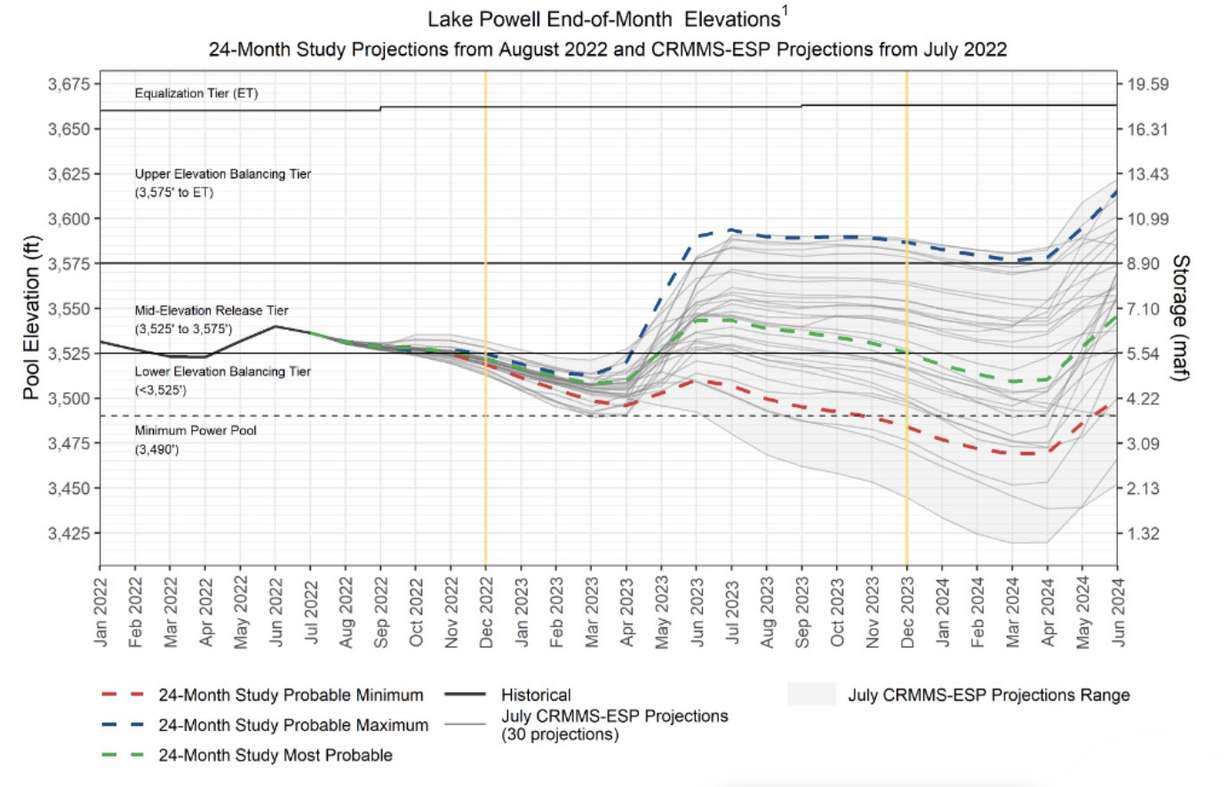

The Department of Interior and Bureau of Reclamation released on Tuesday a 24-month survey for Lake Powell, by the Utah-Arizona border, and Lake Mead, by the Arizona-Nevada border, including a 2023 operational plan for both reservoirs. The two reservoirs combined are at about 28% of full capacity.

"Without prompt responsive actions and investments now, the Colorado River and the citizens who rely on it will face a future of uncertain conflict," said Tanya Trujillo, the Department of Interior's assistant secretary for water and science. "That is why in addition to encouraging additional voluntary conservation, we have announced certain actions we will begin to take immediately."

The report states that the Department of Interior will evaluate hydrologic conditions in April 2023 with the possibility of limiting releases from the dam to as little as 7 million acre-feet expected to be released next year, as compared to a maximum of 9.5 million acre-feet. In all, the goal is to keep Lake Powell at least 3,525 feet by the end of 2023 to protect a 35-foot buffer between current levels and the level where hydrologic functions are lost.

Meanwhile, the Department of Interior will list Lake Mead and Lower Basin states within what's called the "Level 2a Shortage Condition" for the first time ever in 2023 because of Lake Mead's issues. The document states that Arizona, Nevada and Mexico are facing "required shortage reductions and water savings contribution" of their annual allotment in 2023, ranging from Mexico's 7% reduction to Arizona's 21% reduction.

Fixing Lake Powell

Lake Powell is currently at about a quarter of capacity, dwindling over the past two decades due to historic droughts and low runoff conditions. Christopher Cutler, the manager of the Water and Power Services Division at the Bureau of Reclamation, said the Colorado River Basin is currently in the middle of its driest 23-year period on record; the period from 2011 to 2021 is also the driest decade on record.

The Department of Interior's study anticipates levels will reach an elevation of 3,521.84 feet by the start of 2023, about 12 feet below current levels and 178 feet below what's considered a full pool. That number is also only 32 feet above the minimum level for the Glen Canyon Dam to produce power.

The department reduced releases from the reservoir by 480,000 acre-feet earlier this year. Utah and three other states also agreed on a plan in April to send 500,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge to Lake Powell to help Lake Powell's levels. Those measures will improve Lake Powell's elevation by about 15 feet once complete next spring, said Daniel Bunk, the deputy chief of the Bureau of Reclamation's Boulder Canyon Operations Office.

Although Cutler says the most recent "probable" forecast shows runoff at 86% of average — better than this year's percentage of normal — the long-term storage is still expected to drop in 2023. However, there's "significant uncertainty" as to what the future holds for Lake Powell in 2023 and 2024, Bunk says. In addition, the reservoir's issues won't be fixed even if 2023 and 2024 are productive water years.

"While there's a possibility of improved conditions at Lake Powell with above-average inflow next year, it would take multiple years of above-average inflow for (Lake) Powell to recover," he said. "The vast majority of hydrologic projections show that Lake Powell will remain at the same level or continue to decline over the next two years."

In a worst-case scenario, levels could drop below the minimum levels for hydrology by the middle or end of 2023. Bunk warned that yet another dry winter could put the reservoir on that trajectory.

This is why federal experts are exploring a range of options to keep the reservoir at hydrological capacity, while also providing water to surrounding communities, especially Page, Arizona.

Trujillo explained that more types of releases from Upper Basin states could be implemented in the future, like what is currently happening with Flaming Gorge. The bureau will also evaluate if modifications can be made to the Glen Canyon Dam to allow water to be released in areas below any known "critical elevations."

The department's focus is on preserving the infastructure first before any consideration of decommissioning the dam, she added.

"We will rely on our expert technical staff to help us evaluate what additional measures we should be taking to help protect the infrastructure," Trujillo said. "That could include a wide range of options."

Lake Mead has similar woes

While Lake Mead will reach a new level of conservation planning next year, it could get worse after 2023.

"There is a chance of deeper levels of shortage, such as a Level 3 shortage, as early as 2024," Bunk said. "Lake Mead could potentially decline below elevation 1,000 feet with less than 4.4 million acre-feet in storage, which is 17% of capacity, as early as the summer of 2024."

Much like with the Glen Powell Dam, Trujillo said the bureau will review the possibility of modifying Hoover Dam to allow for water to be released at levels below the minimum right now. She added that ensuring that the Colorado River can continue to provide water and electricity for millions of people is an "unwavering priority" of the Department of Interior.

Just the beginning

States in all of the river basins should continue to find ways to conserve water to help protect the declining reservoirs — that's the underlying message of the department report. It comes after the Bureau of Reclamation called on states to reduce consumption by 2 to 4 million acre-feet earlier this year.

The Upper Basin states, which include Utah, did provide a proposal for outlying steps for additional conservation, according to Trujillo.

"We need to make sure that we can see additional conservation in all of the states and all of the sectors," she said.

But some conservation groups argue that the federal projections are too rosy. They aren't as sure that levels will stabilize as some of the projections suggest.

"The bureau continues to be too optimistic in forecasting water flows during this era of aridification. We're disappointed they refuse to take action to protect flows to the Grand Canyon and the Lower Basin by failing to fix Glen Canyon Dam's antique design and cutting water in the basin," said Zach Frankel, the executive director of Utah Rivers Council, in a statement Tuesday.

Officials hinted that steps could be implemented in the future that reduce the share of water that states receive from the river, although most of the actions now center around voluntary conservation and investing in new technologies that reduce water consumption.

Camille Calimlim Touton, the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, contends that Tuesday's report is just the beginning of steps to conserve water so the country's two largest reservoirs can survive.

"The risk that we see to the system is based on the best available science that we've seen and those risks have not changed," she said. "So, today, we're starting the process and more information will follow, as far as the actions we'll take in that process. ... We need to be able to protect this system."