Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah history for KSL.com's Historic section.

SALT LAKE CITY — Do you remember where you were when the Salt Lake City tornado struck?

It was 20 years ago that KSL meteorologist Kevin Eubank recalls turning to a rooftop camera during an afternoon broadcast. He said it was his second day on television as a fill-in weatherman before he was eventually hired full time.

He initially thought the camera showed a microburst heading toward downtown Salt Lake — mainly because it’s Salt Lake and those aren’t out of the ordinary, unlike tornadoes. Seconds later, as he saw the rotation of the storm and power lines being snapped in the frame, he realized what it was.

“All of a sudden, it completely changed everything,” he said. “Meteorologically speaking, it was an anomaly for Salt Lake City because there had been a notion with mountains surrounding us ... you don’t get tornados here. This day, Aug. 11, 1999, kind of dispelled that and really provided a case study that, no, you can get tornadoes that form within mountains.”

Aug. 11, 1999

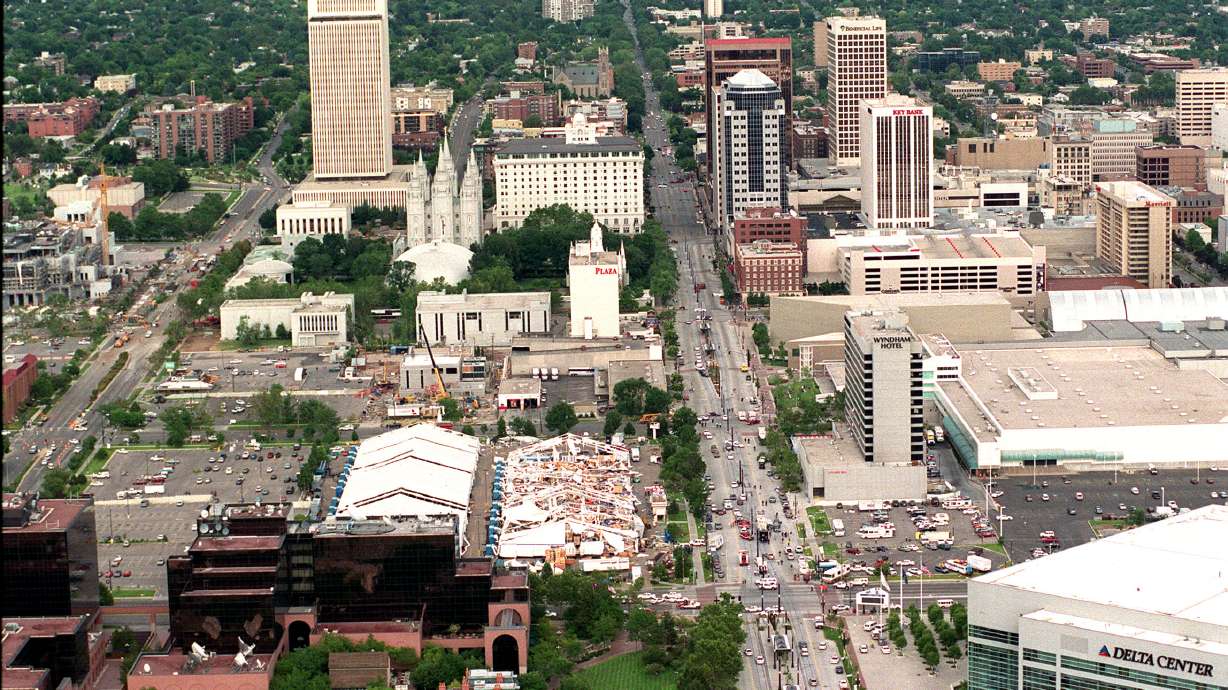

The Salt Lake City tornado officially touched down about 12:41 p.m. in the city's Poplar Grove neighborhood. In a span of about 14 minutes, the tornado crossed I-15, passed by the then-called Delta Center, through a parking lot across from the Triad Center where Outdoor Retailer had tents set up at the time, past Temple Square and the Kearns Mansion, and across the Utah Capitol lawn and Memory Grove before it ended in the Avenues neighborhood.

In all, it cut through 4.25 miles during those 14 minutes. At its peak, the twister reached F2 on the Fujita scale (113 to 157 mph), according to National Weather Service data first released weeks after the devastation.

Once the tornado left the view of the rooftop camera, Eubank said he instantly tried to track where it could be headed and alert as many people as possible. Alerting people who were away from TV screens wasn’t as easy as it is now, thanks to cellphones. Eubank explained it’s also harder to track tornadoes in Utah because the cells where tornadoes form may be too small to see on Doppler radar as compared to the major storms that sweep across the midwest.

On Aug. 27, 1999, National Weather Service officials echoed this problem. A Deseret News article from that day quoted an NWS official who said there was nothing abnormal from the radar that could have alerted people sooner.

The tornado created panic throughout the city as it passed through. One home video sent to KSL that day showed a group of people running for shelter at Temple Square. It was the same scene throughout the tornado’s path.

“We ran across the street, just grabbed a tree, and my legs were in the air at one point. I was just holding on as hard I could,” one witness told KSL TV after the tornado was over on Aug. 11, 1999.

“I didn’t have enough time to get inside. I kind of dove in the corner here,” a woman who was bloodied by a fallen roof also told reporters that day. “I was on the patio and the roof came down on me.”

There was confusion in the KSL Broadcast House at the Triad Center, right across the street from the tornado’s path. KSL Newsradio news director Marc Giauque was a producer working that day. Twenty years later, he remembers seeing a storm was coming in that afternoon.

“It got really dark. We heard a rumbling, but it wasn’t like as if we were in a house and people describe (hearing a sound like) a freight train coming by,” he recalled. “We saw the trees bend over. We saw stuff flying. It looked to me like a microburst. I don’t think I realized how serious it was until we looked outside after it went through and saw the destruction and realized it was happening all over.”

He remembers an all-building alert coming on shortly after the tornado passed, which shows how difficult it was to alert in advance due to the tornado's speed. It was also pretty clear the Outdoor Retailer tents were hit hard, he added.

Many bystanders rushed to the tents and tried to render aid to those who were inside at the time. Allen A. Crandy, a 38-year-old contractor from Las Vegas attending the event, was the tornado’s lone fatality. He was just the state’s second known tornado fatality on record; the first since a girl was killed in 1884. According to news reports, 49 others were rushed to hospitals that day while many more were treated on the streets.

The twister also caused more than $170 million in damage throughout the city and uprooted or severely damaged about 800 trees, according to the Deseret News. It remains one of the most remembered moments in the city’s history because it was such a surprise.

“Nobody expected it,” Giauque said. “You just don’t expect a tornado in downtown Salt Lake.”

Why the surprise of the 1999 tornado may never be matched

The 1999 tornado was the costliest in state history, but far from the first. Utah averages about two tornadoes per year. But the Salt Lake City tornado taught meteorologists about rarely-seen characteristics, such as climbing elevation.

“It didn’t change the entirety of how I view weather, but it most definitely opened my eyes that anything is possible," Eubank said.

However, the surprise of the Salt Lake City tornado is likely hard to match now that it has happened. In addition, technology has improved in 20 years that has made tracking weather easier — and the same can be said about instant mass communication. Today, people are constantly alerted through push notifications and emails when severe weather is happening.

Aside from learning about the possibility of tornadoes, Eubank said his biggest takeaway from the storm is how Utahns came together to help each other out in a time of need. He said that and the education that tornadoes can happen in the city are what he believes is the tornado's legacy.

"I think the legacy is we came together and (tornadoes are) possible," he said. "If it's possible, there's a chance it will happen again. We need to be more prepared, and I think we have come a long way with having the tools ready to be prepared for the next tornado that comes."