Estimated read time: 10-11 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — As she watches the teenagers who come and go from the legal clinic where she volunteers, Nicole Lowe sees reflections of herself.

Though she now holds the title of assistant attorney general in the state's child protection division, Lowe's young life was more like those of the teens she serves. At 14, she was a runaway entranced by a gothic cult, roaming Salt Lake City, battling psychological demons in the time between hallucinogenic highs.

It's a story Lowe has never sought to hide, both in her personal and professional life. But now she is sharing it in a way she never has before, recounting her three years on the streets through her memoir, "Never Let Me Go," published last month.

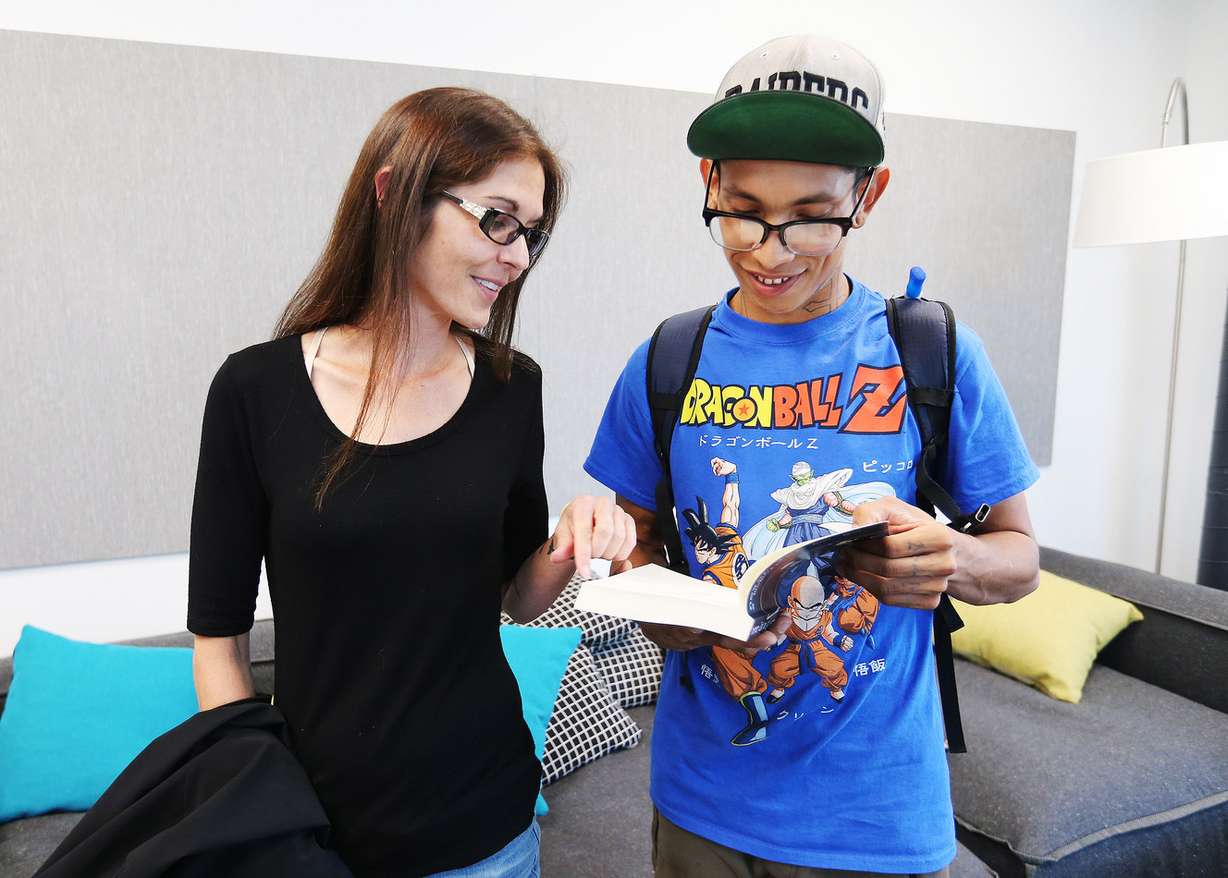

Lowe carried a copy of the memoir as she walked through the Volunteers of America–Utah's Youth Resource Center on Thursday. Met by a 22-year-old client named Gabe who she has consulted with for the past few years, Lowe explains that the reporters with her have come to talk about the book, giving a brief explanation of her backstory.

The young man is stunned.

"That surprises me a lot. I didn't expect that," Gabe says, eyeing the cover photo of a teenage Lowe masked in pale powder, thick eyeliner and black lipstick.

"That's why I'm here," Lowe responds.

A story to tell

Lowe wrote her book for families. If the story helps one child realize there is hope beyond the darkest moments in life, or one parent decide not to give up on a wayward son or daughter, then sharing her most personal experiences will be worth it, she said.

She also wrote it for her two sons, who she has sought to give a life that is vastly different from the one she led at their age.

Any number of factors — abuse, depression, poverty, addiction, mental illness — can lead a teenager to homelessness. Looking back, Lowe says it was a combination of depression and loneliness in the absence of two working parents that prompted her own sudden and dramatic shift.

"I felt pretty invisible as a child, and I think part of my whole rebellion was to bring notice because I was done being the perfect kid," she explained. "I was a straight-A student. I was active. I was following home rules. I never did anything wrong, so when I finally said 'enough is enough,' I went extremely the other way just to see if I would get noticed, and I don't think my parents knew what to do with me."

In her book, Lowe describes drinking and experimenting with drugs as early as age 13. By 14, she was disappearing from home for days at a time, panhandling, partying and getting high. Disguised in her gothic makeup, Lowe believed she, her brother, her friends, and her abusive older boyfriend had been torn from a mystical world and were now living a sham life they called "The Charade."

"I think a lot of people are fascinated by the cult aspect of the book and how that came about," Lowe said. "I think that people are very surprised where I'm at with everything that I've been through."

While on streets, Lowe was raped, sending her spiraling even further. Those memories are some of the hardest for people to read, she says.

Lowe's memoir follows as she left Salt Lake City, stealing a car with a group she had just met and fleeing to California. She eventually left her gothic beliefs behind as she hitchhiked between Oregon, Washington, Montana and later Salt Lake City again, living in parks, woods and under freeway overpasses. To get by, she shoplifted, panhandled and dealt drugs.

Everything changed when Lowe got pregnant at 16, choosing her son over her nomadic lifestyle.

"When I first started working on (the book), my oldest son was the same age that I was in the book, so for me, that was like, 'Wow, how different is his life than mine?" Lowe said. "I was proud of that, because I wanted his life to be different than mine. I didn't want him out on the streets. I didn't want him involved in drugs or gangs or cults or anything like that."

'The parent table'

A high school dropout, Lowe worked following the birth of her son to catch up, finishing just one term after what would have been her graduating class. Later adding a second son from a short-lived marriage, Lowe continued with her education, attending Salt Lake Community College and the University of Utah to earn degrees in psychology and law.

In the courtroom, where she frequently deals with child custody and welfare issues, Lowe often thinks she could have easily ended up on the other side of the cases she litigates.

At "the parent table," as she calls it, she sees mothers begging to keep custody of their children, even as they battle addiction, abuse and criminal convictions.

She could have been one of them.

Ultimately, Lowe's experiences haven't changed the decisions she makes in her cases, she says, but it gives her deeper compassion and an ability to communicate difficult situations on all sides, she said.

"It helps me to explain things to other people who are involved in the system, whether it be my caseworker … or the other attorneys who are in there, or the way that I argue something or frame something to the court," Lowe said. "All of that changes when I can make those connections between my life and theirs."

Lowe knows those parents arguing to reclaim their custody rights, even as she challenges them, have no idea the empathy she has for them.

While the guardian ad litem argues exclusively for the interests of the child and defense counsel is interested solely in the parent's wishes, Lowe looks for ways to serve both, keeping families together wherever possible.

"We (the state) take into consideration what that parent is doing and saying and all of that, and their issues, and then also the needs of the child," Lowe said. "I think I'm able to do more things for these families when I represent the state."

Having repaired her relationship with her own mother, Lowe emphasizes her advice to parents who have custody of their children, but see them falling into destructive behaviors. Keep the door open, she says, whether that means not locking them up when they rebel, or allowing them to come home again if they leave.

"What I would tell a parent is never close the door. Never give up on your child. They can and will pull through it if they have a support system in place, and if they know that home is always there. They will be much more likely to pull out of it, even if it takes years and years," Lowe said.

"If you close the door and you push them away, or if you try to lock them in and hold onto them so tight and make them what you want them to be, that doesn't work, and they'll just push back even more."

Two families

In addition to her time in the courtroom, Lowe founded the legal clinic at the Volunteers of America-Utah's Youth Resource Center, now housed in the center's thriving new facility at 888 S. 400 West. She has an office but usually ends up simply hanging out in the bright common areas and dining hall as she answers the teens' questions about their truancy issues, debts, evictions or criminal charges.

"This was my community, this was my family when I was out on the streets. It was these kids with these life experiences. We were kindred spirits, and I wanted to give back to that specific community because they gave me so much," Lowe said.

It's where she has met youth like Gabe, the young man she presented her book to on Thursday.

"It makes a lot more sense why she's here with us, why she's helping us out," said Gabe, whom KSL/Deseret News agreed to identify only by his first name. "She wants us to do better. She wants to give us the push that we need, like every other staff member here."

On the streets periodically since he was 19 years old, Gabe would drop by the Volunteers of America's old Youth Resource Center on State Street, mostly to hang out and get some food, he said.

At first, he didn't take advantage of other services the center provided. When he did, he was amazed at the difference it made.

"They helped me get into a transitional home," Gabe said. "I was there for a year and three months. I did well there. I had a job. I had everything going for me."

Gabe moved from there to live with the mother of his child and her family, but later found himself back on the street. Alone and depressed in a motel room, he felt himself drawn again toward old addictions.

"I was really vulnerable and I needed help," Gabe said. "I came to the new center because it was a shelter as well, and I know I can come here and talk to the advocates here."

With its clean, modern facility and overnight services specifically for clients age 15 to 22, Gabe calls the new youth resource center "summer camp." It's a place where he feels safe and strong enough to fight his addictions.

Sarah Strang, the facility director, said the center is meant to be a safe place where youths are also connected with services they need.

"It's been interesting to see how much the youth like to be here," Strang said of the new facility. She went on to say, "We're incredibly lucky to be able to provide shelter to these youth, and being able to watch supports be put in place in a way that allows them to overcome hurdles they have faced in their life is amazing."

The 30-bed center opened in May thanks to the support of a number of community partners, Strang said.

During the day, any youth can can come in for food, laundry, showers, counseling, legal help, internet access, or just a comfortable place to read a book and take a nap. There are also volunteers who teach job skills, help with resumes and connect clients with family, treatment or housing programs.

Being able to offer shelter to homeless youths for the first time has been a vital addition, Strang said. She hopes the program will continue moving forward, eventually offering more beds — the winter will pose capacity challenges, she notes — and gender- or need-specific facilities.

Lowe hopes the legal clinic will grow as well, eventually becoming able to connect youths with legal representation that will stay with them through the entire litigation process, offering more educational programs, and establishing a fund to help youths who are trying but struggling to pay restitution in their cases.

When she leaves the resource center at the end of the day, Lowe talks often with her own children and the young people like Gabe she has met.

"I definitely talk to them about it … so that they see people and especially kids out on the street that they don't feel revulsion. It's more compassion and caring and wanting to reach out to them," Lowe said.

Far from the stereotypes so often applied to homeless youths, Lowe said she wants her children and others to realize the young people she has met through the years are ambitious, motivated, hopeful and have a strong will to survive.

"If we can all just get together and support them, they can do great things," she said. "They're determined to move forward, and they keep trying."

The greatest victory, she says, is seeing families succeed and watching the youths she meets proactively get jobs, find housing and stabilize their lives.

"To see them go from ripped up, dirty street clothes to a button-up shirt and slacks and just smiling, is the best reward. They're so excited that they're actually doing it," Lowe said. "There's nothing better than that."

Photos

Show All 12 Photos