Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

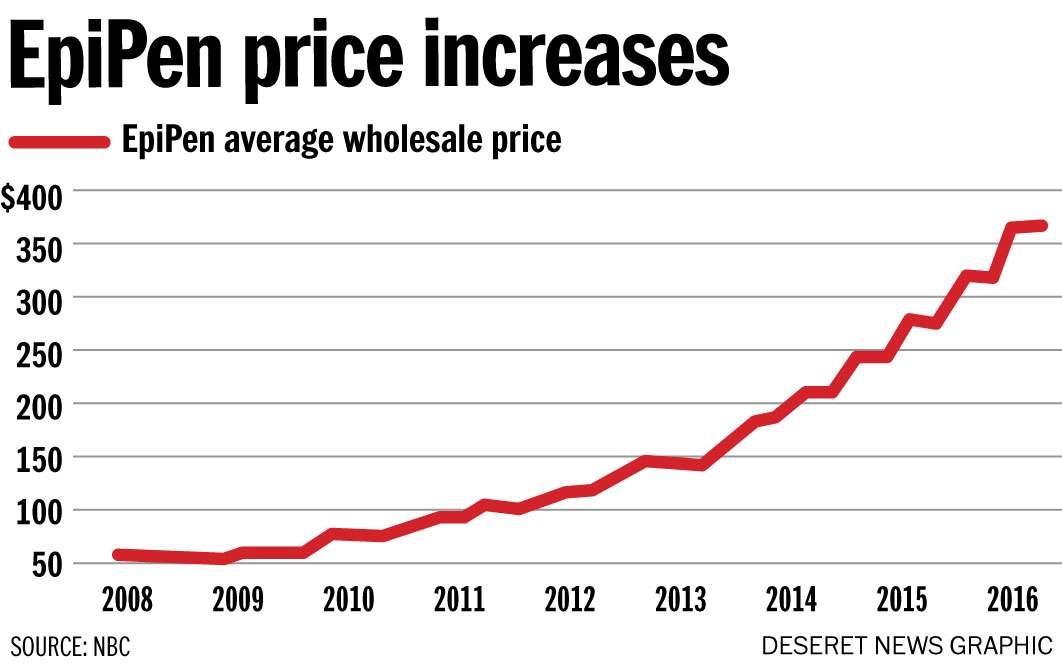

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah parents say they are unsatisfied by a drug company’s efforts to lower the price of the EpiPen, an epinephrine auto-injector for severe allergic reactions that has quadrupled in price since 2007.

With Congress calling for an investigation and stocks dropping, pharmaceutical company Mylan said it would provide a $300 coupon and boost its assistance program for uninsured patients.

"No one's more frustrated than me," CEO Heather Bresch said on CNBC on Thursday, explaining that "there are four or five hands that the product touches and companies it goes through before it ever gets to that patient at the counter.”

"This isn't an EpiPen issue. This isn't a Mylan issue. This is a health care issue," she added.

It is unclear how big of an impact Mylan's actions will have on patients.

Those on government plans like Medicaid or Medicare cannot use the coupons. For those who can redeem the coupons, the final price may still be prohibitively high. And for those with income levels above 200 percent of federal poverty level — which Mylan plans to double to 400 percent — will not qualify for the assistance plan.

Kimberly Faerber, a mother of three from American Fork, said her family is on a high-deductible plan that does not cover prescriptions. In the past, Faerber said, her insurance company and local pharmacy have not accepted the Mylan coupon.

"The insurance company said it was up to the pharmacy as to what discounts they might be offering," Faerber said. "And then when I called the pharmacy … they basically said it's up to Mylan."

An EpiPen pack for each of her daughters — ages 14 and 9 — can easily cost $1,200, Faerber said. And because they expire quickly, the Faerbers have to restock every year.

"It affects everything we do,” Faerber said. “That's how I send them out into the world to live normal lives, is the EpiPen. That's how they participate in day-to-day living, school, camp.”

Others say the EpiPens are too expensive, even with the coupons.

Julie King, a Saratoga Springs mom who watched Bresch's 18-minute interview, said she found the chief executive’s comments “offensive and condescending.”

Even with her insurance plan and a $300 coupon, King said, an EpiPen pack will cost her $450. And her teenage daughter, who has gone into anaphylactic shock six times, needs more than one pack so she can keep them at home, at school and on her person, King said.

“The idea that (Bresch) has more concern and frustration than those millions of parents that fight every day to keep their children alive is condescending and ridiculous,” King said.

"To me, it's not a solution. It's a PR move," she added.

Erin Fox, the director of drug information at University of Utah Health Care and a drug pricing expert, is inclined to agree.

She said drug coupons — which have surged in popularity the past few years — are largely a marketing strategy for the pharmaceutical company.

If patients are so turned off by the price that they switch to a generic or forgo the medication altogether, the company gets nothing. But if patients can be insulated from the true price, they may continue to purchase the expensive product.

Meanwhile, insurers will foot the bill — and, according to critics, will respond by raising premiums and co-pays on everyone.

"I agree the system is broken," Fox said. "But there's no reason why they can't lower the price."

Even families that have successfully used the coupons say they continue to harbor concerns.

David Martin, of Eagle Mountain, said he got the EpiPen pack for free after the coupon took care of his $50 copay. Still, he is worried that Mylan will continue to raise the prices and that the EpiPen may become out of reach for his 7-year-old son, who is severely allergic to milk and peanuts.

"(My insurance company) could come out next year and say, 'Yeah, we're not covering that,'" Martin said. "Or they might cover half as much as they cover this year."

Alternatives are few and far between. Auvi-Q, a competitor, was pulled off the market after a recall last year.

Adrenaclick, a generic epinephrine auto-injector, is available but requires a prescription from a doctor, many of whom are not aware that it exists. Even then, it is not always much cheaper than the EpiPen.

Faerber said she might look into other options legally available to her, like buying EpiPens from Canada.

She also watched CNBC's interview with Brecsch and said she was unimpressed.

"They have a choice," Faerber said. "They're choosing to play in the health care system that they say is broken. If they want to fix it, they could be the ones to make a stand. Reduce the price."